© Joachim Löning

When it comes to the integration of the new ESG (Environmental Social Governments) regime into the architecture of investment advice, it is important to consider all phases and aspects of the customer buying cycle. In technical terms, the EU catalogue of criteria known as “ESG taxonomy” is an additional set of auxiliary conditions for portfolio advice. The social and psychological aspects of these additional conditions are essential for the investment decision process; we highlight these below.

Portfolio Coordinates in Upheaval

People, organisations and institutions constantly give signals to one another through their choice of possessions. This serves to balance an image of oneself with the image one intends to project. We know that this symbolic functions of goods and possessions goes far beyond the demonstration of social prestige and representation: it extends to mental hygiene, i.e. in the form of a clear conscience. Therefore, transparent and comprehensible investment decision-making processes are of central importance. A conscious, perhaps even mindful investment decision is the occasion, expression and medium of an intended reduction of cognitive dissonance, and, at best, can be a real added value for the individual. ESG experts are already successfully monetizing this. Affiliation, status, and a clear conscious have a widely observed intrinsic value today. The insight is also evidenced though numerous neologisms: it is not without reason that there is now talk of, for example, “flight shame” and “train pride”. If at all, it is only a small step that is missing before investors realise that they can also be ashamed of the ownership or certain returns in their portfolio – and indeed they should be, as regulators have already taken up the cause of “redirecting private capital flows towards more sustainable investments” (European Commission 2018).

Investment products also stand for values and lifestyles, and they can be classified and differentiated accordingly. By representing identity, they have not only a financial value, but a cultural and individual value, too. Our portfolio is close to us and it influences our experience (am I guilty?), and our behaviour (what’s going on there?). The active and reflective selection of investments on the basis of diverse ESG criteria holds the chance – and hope – of exerting a controlling influence on this highly subjective investor experience, which is fed by the conflict of personal wishes, socially accepted behaviour and environmental experiences. What is all well and good in a portfolio is currently being renegotiated.

ESG on Everyone’s Lips

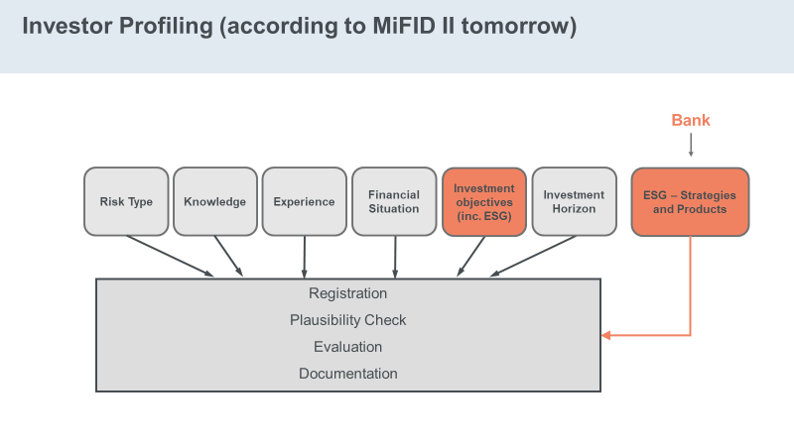

The interface is where money and world meet and interact, where bank (advisor) and customer interact. Customer profiling has not always been a permanent feature of this process but, at least since its introduction by the regulator, it has become decisive for the correct fit between a bank’s offer and a customer’s need. It has become impossible to imagine this interface between money and world without the theme of ESG. The European Commission makes no secret of its explicit objectives around which this EU governance project is all about: (see ESMA Final Report: “ESMA’s technical advice to the European Commission on integrating sustainability risks and factors in MiFID II” 30.04.2019, ESMA35-43-1737).

- Reorient capital flows towards sustainable investment in order to achieve sustainable and inclusive growth;

- assess and manage relevant financial risks stemming from climate change, resource depletion, environmental degradation and social issues; and

- foster transparency and long-termism in financial and economic activity.

The measures recommended by ESMA concern the entire value chain:

- …identify (…) the potential target market (…) and specify the type(s) of client for whose (…) ESG preferences (where relevant), the financial instrument is compatible. (Article 9(9) of the MiFID II Delegated Directive)

- …determine whether (…) the financial instrument’s ESG characteristics (where relevant) are consistent with the target market (…). (Article 9(11) of the MiFID II Delegated Directive)

- …review (…) if the financial instrument remains consistent with the (…) ESG preferences (where relevant), of the target market (…). (Article 9(14) of the MiFID II Delegated Directive)

- …have in place adequate product governance arrangements to ensure that products and services (…) are compatible with the (…) ESG preferences (where relevant), of an identified target market and (…) the intended distribution strategy. (Article 10(2) of the MiFID II Delegated Directive)

- …review the investment products (…) and the services they provide on a regular basis, taking into account (…) whether the product or service remains consistent with the (…) ESG preferences (where relevant), of the identified target market and whether the intended distribution strategy remains appropriate. (Article 10(5) of the MiFID II Delegated Directive)

Ecological design principles should therefore be incorporated into the design and sale of investment products in order to create and maintain “suitability”. In some cases, this integration of a new layer of customer suitability is perceived as annoying, even intrusive. Furthermore, what the consideration of ESG criteria means for the risk and performance of investment instruments is also controversial. If the ESMA’s recommendations are accepted by the European Commission, the industry will have to face far greater challenges than simply having to ask clients additional questions in the profiling stage. Yet, perceived from a different standpoint, the issue of ESG affects us all: it is therefore ideally suited to create a shared experience in which advisor and client can find themselves on the same page as partners. In addition, in the cases of long-term investments there is much to suggest, in view of the current changes in thinking, that ESG criteria can not only prove to be performance drivers but can also help to reduce reservations about financial markets. In what follows, we would like to highlight a fundamental difficulty in investor profiling, one that is particularly significant due to the topicality and emotional climate of the theme of ESG.

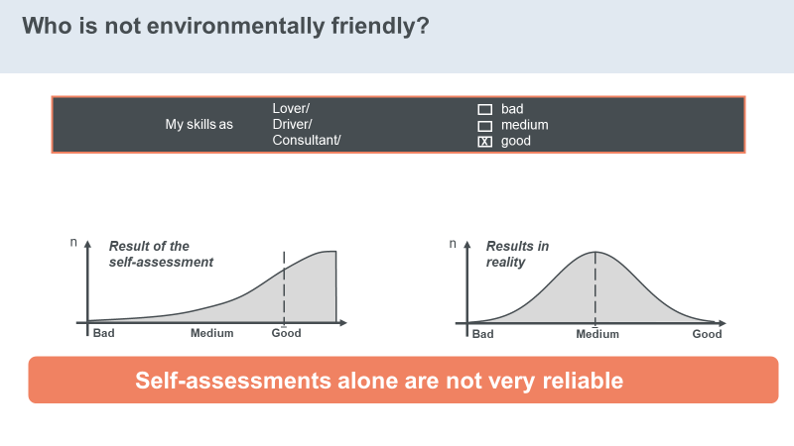

Investor Profiling: Measurement vs Self-Assessment

If you are really interested in the makeup of an investor’s personality, you need suitable measuring instruments. For example, the self-assessment of risk personality is a poor measurement because self-assessments are naturally distorted by the effects of social desires and cognitive dissonance – they are demonstrably not very meaningful. Have you ever wondered how studies, for example, have managed to reach conclusions that men in Germany, according to their own statements, have slept with an average of ten female partners in their lifetime, but women only with five? Or that men state that they have sex on average 1.2 times a week, but woman on average only 0.9 times a week. And also, that other studies indicate that both figures are, in fact, exaggerated?

Fortunately, we know that a normal distribution can be expected when a variable in influenced by numerous, independent and inter-dependent factors (cf. Preiser 2003). On the basis of this knowledge, test batteries can be created that satisfy the quality criteria of objectivity, validity, and reliability.

Fortunately, we know that a normal distribution can be expected when a variable in influenced by numerous, independent and inter-dependent factors (cf. Preiser 2003). On the basis of this knowledge, test batteries can be created that satisfy the quality criteria of objectivity, validity, and reliability.

Our Interim Conclusion: Opportunism vs. Conviction

There are many ways in which to take ESG criteria into account when preparing an investment recommendation. These differ fundamentally in terms of both their objectives, and their consistency – as indeed investors do.

In one of our following blog posts, we will discuss common and possible approaches to ESG integration, their consequences for the portfolio and, in particular, software-supported portfolio consulting.

Related Links: